You new American beer stein collectors might think the giving a beer stein to celebrate a death as being a bit strange?

Well we aren’t going to get out of here without facing it, so the older Germans (early 1800’s in particular) being realistic, created a whole sub-set of beer steins to celebrate / remember the occasion of someone’s death. There is usually a saying / monument and / or angel associated with the totally engraved scene. They were presented to the grieving family from friends and therefore took a place of honor on a mantel or other prominent spot in the house.

Four different styles of engraved blown clear glass Death Memorial beer steins. All Circa 1820- 45. The lids are different as are some of the bases. On the far left the stein has [a] rows of cut design engraving setting off the scene, [b] On the bottom, inserted air holes in a circular pattern. The second from the left has a sunburst made from a mold pushed up into the base while the glass was still hot. The other differences are pretty obvious. [FWTD]

Details of two of the above steins in the window. [L] Angel holding a monumental stone ball with wording. [R] Monument with a large urn on top, flowers and “In Memory” engraved.

.

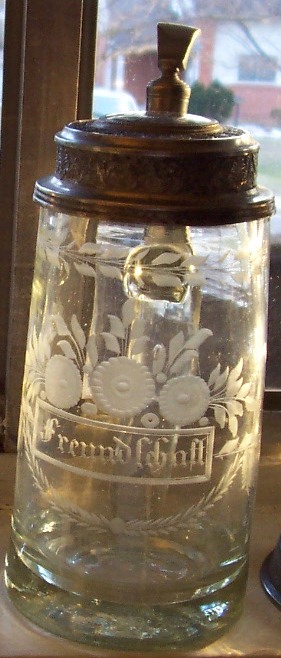

Detail of third from left above. A .5 liter blown clear glass. It comes with a pewter “shoehorn” thumblift which dates it to about 1835 – 50.

A Death Memorial Steins, not shown above. This one has a marked .800 silver lid, the pressed-in-mold designed base, and just the one, top “diamond cut” rib. The deceased’s name is in the center of the monument with a large bouquet of flowers on top. [FWTD]

BUT NOWADAYS:

In the USA this custom of memorializing a death has changed and has overtaken out highways! Here’s some of the history behind it.

A “roadside memorial” is a marker that usually commemorates a site where a person died suddenly and unexpectedly, away from home. Unlike a grave site headstone, which marks where a body is laid, the memorial marks the last place on earth where a person was alive – although in the past travelers were of necessity often buried where they fell.

Usually the memorial is created and maintained by family members or friends of the person who died. A common type of memorial is simply a bunch of flowers, real or plastic, taped to street furniture or a tree trunk. A handwritten message, personal mementos etc. may be included.

More sophisticated memorials may be a memorial cross or a plaque with an inscription, decorated with flowers or wreaths. (which is exactly what the Germans did on their steins = the message is the same, just the material has changed.)

In doing research for this article I found this reference to be extremely interesting:

The custom of marking the site of a death on the highway has deep roots in the Hispanic culture of the Southwest, where these memorials are often referred to as Descansos (“resting places”).

Traditionally, Descansos were memorials erected at the places where the funeral procession paused to rest on the journey between the church and the cemetery. The association thus created between the road, the interrupted journey, and death as a destination, eventually found expression in the practice of similarly marking the location of fatal accidents on the highway.

“The first Descansos were resting places where those who carried the coffin from the church to the camposanto paused to rest. In the old villages of New Mexico, high in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains or along the river valleys, the coffin was shouldered by four or six men.

“Led by the priest or preacher and followed by mourning women dressed in black, the procession made its way from the church to the cemetery. The rough hewn pine of the coffin cut into the shoulders of the men. If the camposanto was far from the church, the men grew tired and they paused to rest, lowering the coffin and placing it on the ground. The place where they rested was the descanso.

“The priest prayed; the wailing of the women filled the air; there was time to contemplate death. Perhaps someone would break a sprig of juniper and bury it in the ground to mark the spot, or place wild flowers in the ground. Perhaps someone would take two small branches of piñon and tie them together with a leather thong, then plant the cross in the ground.

“Rested , the men would shoulder the coffin again, lift the heavy load, and the procession would continue. With time, the descansos from the church to the cemetery would become resting spots.

. . .

“Time touches everything with change. The old descanso became the new as the age of the automobile came to the provinces of New Mexico. How slow and soft and deeper seemed the time of our grandfathers. Horses or mules drew the wagons. ‘Voy a preparar el carro de vestia,’ my grandfather would say. I remember the sound of his words, the ceremony of his harnessing the horses.

“Yes, there have always been accidents, a wagon would turn over, a man would die. But the journeys of our grandfathers were slow, there was time to contemplate the relationship of life and death. Now time moves fast, cars and trucks race like demons on the highways, there is little time to contemplate. Death comes quickly, and often it comes to our young. Time has transformed the way we die, but time cannot transform the shadow of death.”

“I remember very well the impact of the car on the people of the llano and the villages of my river valley. I remember because I had a glimpse of the old way, the way of my grandfather, and as a child I saw the entry of the automobile.

“One word describes the change for me: violence. The cuentos of the people became filled with tales of car wrecks, someone burned by gasoline while cleaning a carburetor, someone crippled for life in an accident. The crosses along the country roads increased. Violent death had come with the new age. Yes, there was utility, the ease of transportation, but at a price. Pause and look at the cross on the side of the road, dear traveler, and remember the price we pay”.

“Introduction/Dios da y Dios quita”, from “Descansos: An Interrupted Journey”, by Rudolfo Anaya, Juan Estevan Arellano and Denise Chavez (Del Norte , 1995).

(Taken from: http://webpages.charter.net/dnance/descansos/)

Below: A couple more from the Smith collection:

A very detailed monument, small boquets of flowers along the top, and small oval cuts on the bottom make this a very nice example. This one comes with a “flat” (not semi-round) handle throughout but really obvious at the top, so the circa is 1810. [FWTD]

Small cut ovals onthe sides and smaller ones at top. An acorn thumlift, and semi round handle indicate this one to be circa 1835-45. [FWTD]

A monument, bird, flowers and nice diamond cutting on the bottom third of the body. A very different older looking style thumblift, but with a rounded handle. Circa 1840-50. [FWTD]

.

Detail – Showing the superb wheel cutting that can be found on some of these steins.

![1 - MEMORIAL STEIN - JUDY'S 3-07 NOW MINE [question]](http://www.steveonsteins.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/1-MEMORIAL-STEIN-JUDYS-3-07-NOW-MINE-question.jpg)

But then again, some are far better engraved than others.Compare left to right. [L= SA], [R= JS]

A few more of these type of beer steins from recent USA stein auctions:

![MEMORIAL STEIN .5 LITER SOLD ONLY $276 [CORRECT] TSACO 2010](http://www.steveonsteins.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/MEMORIAL-STEIN-.5-LITER-SOLD-ONLY-276-CORRECT-TSACO-2010.jpg)

Death memorial stein. .5 L engraved clear glass, Bohemia probably. Circa 1820 – 50. The arrows in the quiver are a different touch, which I assume mean” Cupid’s Arrows” (= “Love.”) [tsaco ]

Death memorial stein. .5L, blown, clear glass, cut design on top body band, engraved memorial with an large urn on top. Pewter lid with the “kissing doves” thumblift (= Love). Circa:1820 -45, [tsaco]

![(- memorial hate it [q] Glass stein, .5L, blown, wheel-engraved, early 1800s,](http://www.steveonsteins.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/memorial-hate-it-q-Glass-stein-.5L-blown-wheel-engraved-early-1800s.jpg) [tsaco]

[tsaco]

[END – SOK – RD – 20 -Dxx]

“Good health is merely the slowest possible rate at which one can die.”

“Good health is merely the slowest possible rate at which one can die.”

Leave a Reply