A S.C.I. member and member of Gambrinus Stein (Collecting) Club of Virginia, Maryland and DC.

As I have become a slightly more than a novice stein collector, I have found myself thinking about things that I never thought about before. For example, why were these beautiful drinking vessels, steins, pokals, beakers, etc. made from so many different materials?

Then as one narrows the field, and looks at just one material from which steins are made, the questions become more intense. For instance, what is glass and from what materials is it made? Why wasn’t just making a glass vessel enough? Why did most glass makers need to decorate it, too? What were some of the decorating techniques and how were they done?

Answering all of the above is beyond the space allocated for this article. And besides, I don’t have very many answers yet, just lots of questions. However, fellow stein collector Steve Smith shared a book with me recently that was published by the Corning Museum and is entitled Glass of the Alchemists. The book may help me and perhaps some of you readers to find some of the answers—at least about glass. The book is written by several authors who have each prepared certain chapters. It is written in a very scholarly fashion with lots of footnotes and annotations and it contains much food for thought. Glass of the Alchemists is quite a large tome, and I would like to summarize one thread of thought from the book about making colored glass, especially the rich, ruby glass.

In the 16th and 17th Century, one could not go to the department store and get a set of glasses for the table. If one wanted anything made in glass, it had to be commissioned to a glass maker. As any skilled craftsman of his time, the glass maker guarded his “edge” in the marketplace with great care. His “edge” might be the color of the glass he made, the decoration he put on it, clarity of it or any number of things. There was (and is today) no ‘set’ recipe for glass. Then as now each glass producer had his own ‘batch’ formula and guarded it carefully.

As Europe came out of the middle ages into the Renaissance, there was a renewed interest in discovery of new places, new information related to the sciences, and new products–from more powerful guns to delicate silk fabrics. Some of the people who were devoted to the search and testing for new knowledge were known then as alchemists. All were doing experiments to further the body of knowledge in metals, elements, alloys, ores, and chemical compounds as well as math and physics. At that time they didn’t have specific titles or designations such as physicist or pharmacist, but were known as chymeists or alchemists. One of the chief quests of the alchemists was to find the means of turning various metals into gold which they believed could be done. at the time.

Some of the alchemists were true scientists and others were charlatans who claimed to have made the sorcerer’s stone which enabled the possessor to make gold from all sorts of elements and to somehow live an extended life (some very diverse traits for one stone). The sorcerer’s stone was supposed to be a deep ruby color, hard as a rock, and malleable as wax (Quite strange qualities to this author.) Alchemists knew that ruby glass had been made in ancient times, so they worked to formulate it with the hopes that they would be one step closer to (if not the maker of) the sorcerer’s stone and to being able to make gold from other elements.

The scientific alchemists who studied glass and metals often protected their discoveries through secrecy. Little was ever written down for fear that the formulas they developed for glass, colored glass, extracting metals from ores, making enamels, pigments, etc. would be stolen.

But some formulas were written down in the various places and in the various European languages. Enterprising alchemists and interested aristocrats purchased these written formulas which were often written in pamphlets and books. Duke Franz Carl von Saxe Lauenberg in Nauhaus, south of Hamburg, was one who purchased these books and formulas for his library and for his personal study and education. Duke Franz Carl hired Johann Kunckel von Lowenstern (1637? – 1703), an alchemist and pharmacist born near Kiel, Germany, to assist him in going through the Duke’s books and formulas.

Kunckel was a good choice for the position for not only was he versed in chemistry for the time (1600s) he was also the son of a glass blower. From the Duke’s employ, Kunckel was hired by Elector Johann Georg II of Saxony to go through the Elector’s library of alchemical writings and to uncover any secrets they held concerning the making of gold from other materials and the elusive making of ruby glass. With his background, Johann Kunckel was the right person in the right place at the right time again to study of papers in the Elector’s library.

Portrait of Johann Kunckel.from his book, L’Arte vetraria.

Portrait of Johann Kunckel.from his book, L’Arte vetraria.

One of the books of formulas that really seized Kunckel’s interest at the Elector’s library was a book, L’Arte vetraria, the art of glassmaking, by Antonio Neri of Florence, published in 1599. Neri was a priest and alchemist. He traveled extensively back and forth between Italy and Holland. While on these journeys, he stopped and studied glass manufacturing whenever possible. Neri gained a great deal of information concerning the manufacture of glass and its treatments for various purposes. Neri wrote this information into his book which is laden with details for the known methods of making and coloring glass and for using glass to simulate precious stones such as rubies, sapphires, and, of course, the sorcerers’ stone.

Kunckel was an extraordinary scholar of glass. He knew not only how to put together the formulas, and how long to heat them and to what temperature, he also knew how to form the glass into works of art. Most workers in glass knew one set of skills or the other, but since Johann knew both, he directly tested most of the ‘recipes’ in the L’Arte vetraria, which had 133 chapters, sixteen of which were devoted to red glass. Kunckel dismissed many red glass formulas as being wrong or deceitful, and added his expertise and knowledge to others to make them more consistent and sound. Including his own notes, discoveries and amendments to the ‘batch’ descriptions, Kunckel published his version of Neri’s book in 1684, giving both Neri and Kunckel authorship and credit. While correcting some of Neri’s formulas, the author of the chapter on Gold Ruby Glass in the Glass of the Alchemistsstates that Kunckel also published some very incorrect information, presumably to misdirect other alchemists who might try to copy his work.

One of the formulas in Kunckel’s book was his true ruby glass formula with no efforts made to disguise or alter it. Whether he meant to do this is unknown. Ruby glass was known in the ancient world and was supposed to have curative powers. So not only were glass makers looking for the formula for making ruby glass, but those studying glass for its supposed curative powers (doctors, pharmacists, and snake oil salespeople of the time) were also looking for the correct formula. A Hamburg physician, Andreas Cassius, reported in 1676 his discovery of the red coloring properties of a solution of manganese and gold chloride, gold dissolved in a solution of nitric acid and hydrochloric acid (aqua regia). The solution was named for him and is known as “Purple of Cassius.” I was unable to learn how the solution was used by the good doctor, but Johann Kunckel added the mixture to molten glass for the first time in 1680. According to the authors of the Glass of the Alchemists,Kunckel felt he had finally re-discovered the ‘recipe’ for ruby glass. But……

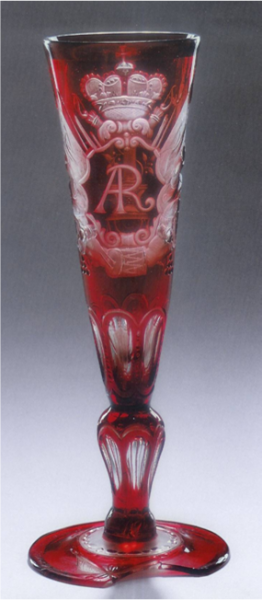

| Covered ruby goblet. Kunckel’s shop, Brandenburg before 1691. Hamburg, Museum fur Kunstund Gewerbe. |

The result was gray glass. As the book’s author’s state, this had to have been an immense disappointment to Kunckel. Producing the “Purple of Cassius” to make the glass was expensive and dangerous because of the corrosive nature of the acids. So to have the expensive batch yield only gray glass, must have been very disheartening, by this authors’ standards. But for some reason, Kunckel chose to reheat the gray glass. It then turned the ruby color and provide the culmination of Kunckel’s life’s work.

Annealing glass is the process of reheating the glass after it has been made into an object. This reheating is a long slow process with an even slower cooling down period which allows the glass objects to soften or relax making them less susceptible to cracking and breaking. Annealing began being widely used in glass production in the late 1600s. So perhaps Mr. Kunckel’s gray glass turned ruby in the annealing oven. No matter how the gray glass came to be heated a second time, it was the key to ruby glass making. Ruby glass has always been used for what the glass industry calls ‘craft production’ rather than in large quantities, due to the high cost of the gold and the delicate mixing process required. The ruby glass is usually hand blown. Few pieces that Kunckel produced from his Brandenburg worksite (ca. 1684) are still in existence. First of all, it is believed by the Glass of the Alchemists authors that only a small number of pieces were made due to the expense of the raw materials. Second, there were many variables to consider with each batch and the color was often not consistent within the piece, was then deemed inferior and destroyed. Third, wars and natural disasters and other reasons for breakage have caused the disappearance of most of his pieces.

The works of art were, of course, made as requested by various rulers and wealthy patrons in Europe. While Kunckel made blown objects from the ruby glass, they were finely and elaborately decorated by what looks like intricate carving or chiseling. In actually, the decoration through shaping was hand formed while being blown and then engraved decoration took place after it had cooled. The workmanship of Kunckel’s ruby glass pieces is very complex and detailed.

Southern Germany, 1695-1700, Museumslandschaft Hessen, Kassel, Germany. Southern Germany, 1695-1700, Museumslandschaft Hessen, Kassel, Germany. |

It wasn’t until 1925 that Richard Adolf Zsigmondy, a Nobel Prize winner in Chemistry, was able to explain that it was the small particles of gold suspended in solution of aqua regia (nitric and Hydrochloric acid mixture) which were responsible for the red color in ruby glass. For the previous 250 years, the formula for ruby glass was known, but how it worked was not understood.

In the 1600s and 1700s, many other alchemists throughout Europe, working separately, tried to develop gold from base metals and to make ruby glass. They had varying results from pink to orange to raspberry to crimson to cranberry to purple as they added oxides of manganese, tin, copper and selenium to the glass batches. The process of making the ruby glass from copper was similar to that of gold as both required an oxide dissolved in an acid to be added to the batch of glass with the copper oxide requiring an oven with reduced oxygen. The cuprous (copper) oxide also required the two part heating process for the red to show. The use of the copper oxide was far less expensive than the “Purple of Cassius” in the aqua regia as well as being a less dangerous mixture. Because copper provides a good ruby color and is less expensive it has become the usual addition to glass when red color is desired.

| Ruby stained clear glass that has been etched through so the clear shows below. |

Eventually in about 1840, Friedrich Eggerman in Haida (now Novy Bor in the Czech Republic) invented a method of staining clear glass surfaces a deep red. He did it with the addition of copper oxide which was painted onto the glass object that then was heated only once to obtain the ruby color, making the process even less costly yet giving the glass a thin coating of a rich ruby color that looked nearly the same until the thin paint became scratched or eroded from handling the object.

The engraving, not etching on this ruby glass goblet is difficult to see because the glass is ruby all the way through so not much extra light comes through the glass.

The engraving, not etching on this ruby glass goblet is difficult to see because the glass is ruby all the way through so not much extra light comes through the glass.

Glass, in general, still has many formulas for making it. How the glass will be used (whether in a stained glass, as part of a thermometer, or as a drinking vessel) will determine the formula that is used to produce it. And ruby glass, specifically, can be made with the addition of oxides of gold, selenium, and copper. Each oxide has properties and costs which affect how it is chosen for various uses. However, the glass made with the gold oxide is expensive and is reserved by fine glass houses worldwide for their special works of art which call for the richest ruby red color.

Faceted ruby glass stein with gold accents and set on lid, from the author’s collection.

Faceted ruby glass stein with gold accents and set on lid, from the author’s collection.

Resources:

Glass of the Alchemists,Dedo Von Kerssenbrock-Krosigk, Corning Museum of Glass

Catholic Encyclopedia, Antonio Neri, CatholiCity.com The Mary Foundation

Glass, Wikipedia.com

Glass Beer Steins, Library, steincollectors.org

Glass Techniques, Library, steincollectors.org

Not in original article, but attributed to Kunckel.

Not in original article, but attributed to Kunckel.

Special thanks to Steve Smith for giving me the book and for his editorial assistance.

[END – SOK]

An all ruby glass poal , unsigned as most and provably by the Egermann workshop, in the “From which to drink” collection. This work of art one comes with a “reducer” on the other side.; which as its name implies reduces the image on the opposite side when looking through it.

_________________________________________________________

Leave a Reply